This month our Brave Story will look different as we celebrate and share experiences from communities that often go overlooked and have recently been under attack: Asian and Muslim Americans. As we celebrate Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, and May 12th marks the end of Ramadan, we felt inclined to not only shed some light on recent developments but to introduce you to some of the guiding lights in both communities.

Did you know that Asia is home to 62% of the Muslim population? Islam has been practiced in China for about 1,400 years, and during my time in Indonesia, I learned that it is the country with the largest Muslim population. Two of the three ladies spotlighted in this feature identify as Muslim, and one identifies as Asian-American.

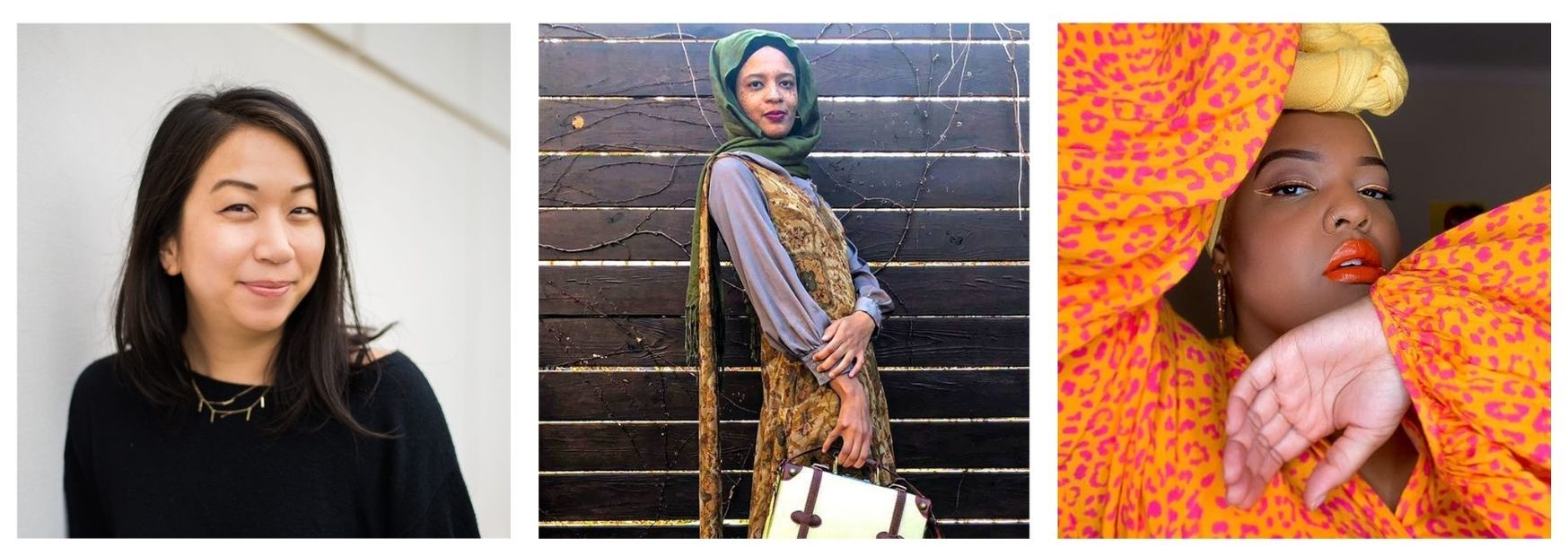

Kareemah Ashiru, also known as the Hijabi Globetrotter, is a storyteller and content creator that shares travel content from a Muslim’s perspective and other underrepresented communities on her YouTube channel.

Author and activist Leah Vernon is an inclusive content creator and plus-size hijabi model. When she’s not posing for some of the top fashion and lifestyle brands, she’s tongue-popping her way to positivity with honesty and vulnerability.

Esther Tseng, a Taiwanese American freelance food writer, based in Los Angeles. Born and raised in the suburbs west of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Esther moved to LA for college and hasn’t left. “I write primarily on the intersection of food and culture and especially beginning in the pandemic, about food justice. The past year has really opened up my eyes in terms of the inequalities in our food systems that have always been there but have become impossible to ignore in light of COVID-19.” From left to right: Esther Tseng, Kareemah Ashiru, and Leah Vernon

From left to right: Esther Tseng, Kareemah Ashiru, and Leah Vernon

We felt it important to feature diverse voices to highlight that no group is a monolith and that in our efforts to support, stand with, and advocate for any marginalized community, we must understand and respect this above all. We hope this conversation helps give an insight into what some of those differences can be and help us see people as individuals, even while speaking, standing up for their communities, protections, and rights.

This is especially important for marketers and brands looking to partner with diverse communities for partnerships and campaigns.

Ramadan Past and Present

When asked how Ramadan in the last two years was different than in previous years, both Kareemah and Leah had interesting perspectives:

Leah: “I’m like the Islamic version of Scrooge during this time,” Leah recently shared on her Instagram. “I’m not the one who sends all the Ramadan Mubarak graphic texts or even prepares for it. Over the past few years, I’ve stumbled into this holy month. There’s always that pang of guilt of why can’t you be devout like other Muslims?”

Kareemah: “Pre-covid, Ramadan was the time where communities became close, acts of kindness were encouraged, and sharing of food with neighbors and friends was an event to look forward to. The month of Ramadan isn’t just about abstaining from the food; it’s also about being grateful and closer to God. Pre-covid, I would try to attain this level of spirituality with the community. We would do it in the form of community prayers and events. I have been lucky to share this moment with communities in New York City, Spain, Ohio, and New Orleans in previous years. Every community has its special tradition, but the ritual is usually the same. We break our fast during sunset, pray our evening prayers, enjoy scrumptious dishes from around the world, connect with people, and continue our prayers. It was truly a memorable month. This year, I am celebrating Ramadan with my family. Ramadan is a very special month, and I feel blessed to be able to spend it with loved ones.”

Leah: “I’ve been traumatized by the Muslim community, to the point that I questioned being Muslim. Not because I didn’t believe, but because other people made it heinous for me. I was never “good” enough. For me, Ramadan was a toxic way to feed my eating disorder. The goal was 20 pounds down by Eid. Or then I’d go overboard trying to abide by every single Islamic rule, and when I broke one, I’d get depressed that I couldn’t please God. That he was disappointed in me. One time, I broke down, and a non-Muslim friend said: ‘I don’t think God is as hard on you as you are on yourself during this month.'”

The Unifier Denier

During Ramadan, the day of fasting ends with a nightly feast. The ritual is about uniting people through food and prayer. The practice of “uniting people through food” is more easily said than done. The phrase is common where food is often thought of as a great unifier. This self-congratulatory rhetoric implies that cooking or consuming food from diverse countries makes you more enlightened or less performative.

For Esther, it’s a bit more complicated than that. ”I tend to be skeptical about the notion that ‘food brings us together because cultural theft and appropriation happen every day.” She added, “Not only is food a great conversation starter and a way to be in gratitude with one another. We all need food to survive. But it’s when it is enjoyed in community with others that we begin to spend time with and foster understanding about those we gather with. When food is used as a tool to achieve community and solidarity with others while giving respect to the origins from whence that food came, nourishment in mind and body achieves its ultimate goal. If food can help bridge gaps, I am 100% behind that.”

Breaking The Minority Mold

Leah has written about the pressure she felt trying to fit the mold of the good Muslim girl and modest wife in her book Unashamed: Musings of a Fat Black, Muslim. Sharing her internal battle and dealing with the judgment and expectations of others, including her community. The Model Minority Myth is a similar type of external and internal pressure.

The Model Minority Myth is a white supremacist concept created to divide people of color by using Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders as a wedge and a distraction from systemic racism. It perpetuates the narrative of the Asian whiz-kid, the Tiger Mom, and the submissive-but-successful dad.

Speak to any member of a minority group, and they will share ways in which they, as individuals, have been impacted by the generalizations and stereotypes that come from the Model Minority Myth and why so many speak up against it. As Esther states, “Proponents of the Model Minority Myth would have you believe that America isn’t racist, because if ‘The Asians’ have found success, then the fault of other minorities’ failure to succeed lies with them. While there are almost 50 countries in Asia from which AAPIs and their ancestors could have emigrated, the Model Minority Myth treats all AAPIs as a monolith, as one class—as if we all are the same and face the same issues.”

She continues, “The reality is that Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders actually experience the most income inequality of any ethnic group in the United States. What they’re doing is putting East Asians who have qualified for immigration from Asia after the Hart-Celler Act of 1965 based on their advanced academic and professional backgrounds out front while erasing not only other minorities but other Asian Americans, such as the underserved Southeast Asian immigrants who have come from war-ravaged countries as a result of U.S. imperialism. Right now, in the AAPI community, it is imperative to address the needs of our low-income elderly, our working class, the Muslim Asian population, Southeast Asians, and South Asians who regularly get erased because East Asians get most of the visibility. We are a very diverse group, and all of us deserve to have our very different needs met.”

Brave World Media: What impact do you think the Model Minority Myth has had on Anti-Asian sentiments?

Esther: “I think it’s had a devastating effect, both on non-AAPI minorities and AAPIs, themselves. It has created division and obscured this country’s racist past and the long history of solidarity and organization that AAPIs have had with other racial groups, including Black-, Indigenous- and Latinx-led coalitions. Examples include anti-war efforts and pro-farm workers’ rights. Some Asian Americans have also believed the lie in trying to achieve their own adjacency to whiteness, so it has caused us to fight with each other, and we as a community still have a lot of work to do in terms of allyship with other BIPOC communities. But along with the past president’s anti-China rhetoric about the ‘Wuhan virus’ or the ‘China virus,’ it’s empowered racists, both marginalized and non-marginalized, to attack us AAPIs simply because of the way we look. It should be clear that the root of all our in-fighting is white supremacy.”

Navigating Hate

Last year all mosques were closed during Ramadan due to COVID restrictions. This year mosques have reopened with heightened awareness about the virus as well as heightened security against Islamophobia.

“My family is still very cautious and taking things slow. This year, we are just spending Ramadan at home,” shared Kareemah.

3,795 hate incidents targeting Asian Americans were reported to Stop AAPI Hate between March 19, 2020, and February 28, 2021. Women made nearly 70% of those reports, while men made up 29%. Stereotyping, exoticization, and racism are just a few of the things at the root of this discrepancy.

BWM: How can we help stop the exoticization of Asian women?

Esther: “Understand that when it comes to Asian women being the so-called “most desirable,” it doesn’t serve as a compliment. It serves a colonizer mindset, and it’s the fruition of a very harmful stereotype about Asian women being submissive. The history of American imperialism in Asia documents how women were sold into human trafficking rings and/or forced into a sex trade expressly to satisfy the American military. Realize that each Asian woman is a unique human being with her own individual characteristics and personality. Each time you find yourself assuming anything about her based on the way she looks. With the Page Act of 1875, Chinese women were expressly barred from immigration because they were “immoral,” but the real reason was, they didn’t want Chinese railroad workers to procreate, polluting the morally superior white population. Work in coalition with other BIPOC to get more Asian writers into our newsrooms and writers’ rooms so that stereotypes are not reinforced in our media and entertainment and that more kinds of AAPIs are not just represented, but the creators of the media we consume and the writers of the stories we tell.”

Kindness, Awareness, & Allyship

Ramadan is the most sacred month of the year for Muslims. 1.6 billion Muslims will observe it in some form. However, only one of the themes is ever openly discussed. I asked Kareemah and Leah to share some of the other themes associated with Ramadan.

Kareemah: “Besides fasting, spirituality is a big part of Ramadan. There is a special night during the last 10 days of Ramadan that every Muslim strives to be present for. We call it Laylatul Qadr. It is said that if one is lucky to stay awake that night and ask God for anything, all their prayers would be answered. In addition, all one’s sins will be forgiven. Other Ramadan themes include: Being one’s best self (i.e., avoid gossiping, give people the benefit of the doubt, etc.), performing acts of kindness, and being generous.”

Leah: “I used to make fun of the Muslims who would hop in during Ramadan and hop out after Eid. I now recognize, maybe that’s the only way they can be present in their spirituality. Ramadan is not a spiritual race. It’s not a burden or a time to ridicule those who choose not to fast the way you do. It isn’t whose a better Muslim contest—who can suffer more while looking better outwardly. There are so many ways to observe this blessed month.”

Kareemah: “Although sadly, I don’t get to share Ramadan with the community at large, this year, I get to be more reflective and focused on my connection to God. An added bonus is being able to share that moment with my parents, something I missed while quarantining alone last year in my New York apartment. I have even pleasantly surprised my parents with some international cuisines I learned from quarantine.”

Allyship looks different for every community. I asked Esther and Kareemah how we can be better allies to both the AAPI and Muslim communities.

Esther: “I think a huge step is to understand that racism also happens to AAPIs; so many believe that that’s not true. With the recent uptick in anti-Asian hate crimes, you can take a few hour-long bystander training sessions by Hollaback—and it’s useful to disrupt attacks on anybody. You can contribute to verified GoFundMe fundraisers for victims of such hate crimes. But in all things, dismantle white supremacy because an attack on any BIPOC is an attack on all of us.”

BWM: What can we do to be better allies during Ramadan?

Kareemah: “Join us to break our fast. We love having everyone involved in Ramadan (Muslim or non-Muslim). If you are an employer or supervisor, be mindful of this month. Because we are usually up all night in preparation for Ramadan and for prayers, some of us might not be as active as we usually are during non- Ramadan months. If you have events that involve food, respect our choice not to eat, we don’t do it to be rude but to practice our faith.”

BWM: What does bravery mean to you?

Kareemah: “Bravery is believing in yourself even when the world doesn’t believe in you.”

Esther: “Bravery means standing up to any and all attacks on people based on any facet of their identity, whether race, gender, class, or orientation—whether you know the victim or not. It’s speaking up for what is right and having the courage to do it, even when it’s scary. It’s not the absence of fear. Bravery, sometimes, is also choosing yourself and what serves you and taking responsibility for it.”