The Brave Story series features different personalities that have demonstrated courage and commitment to a cause, initiative, or movement. We share their stories hoping that their journey and the lessons they learned along the way can serve as motivation and inspiration to us all in whatever path we choose, personally or professionally.

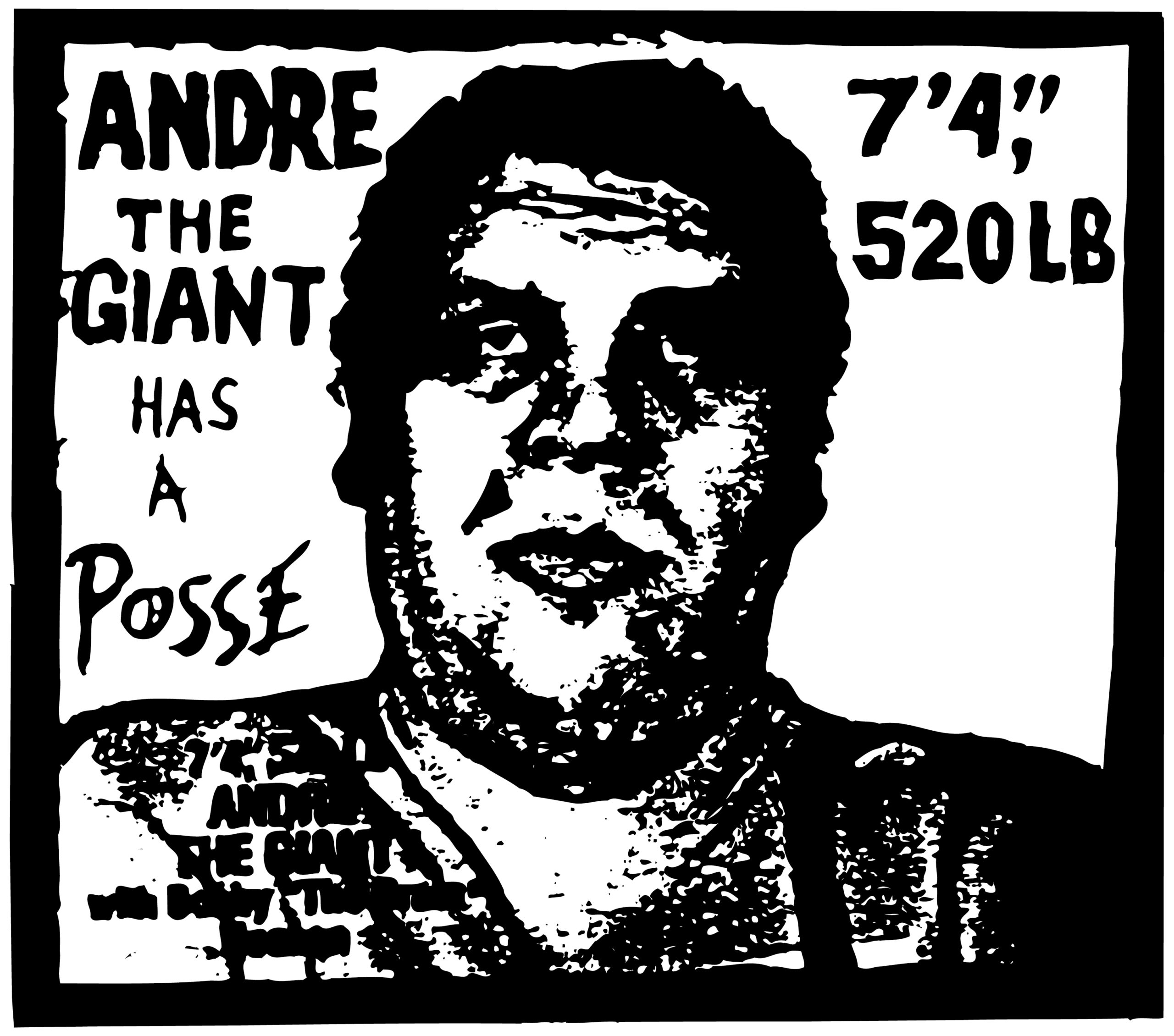

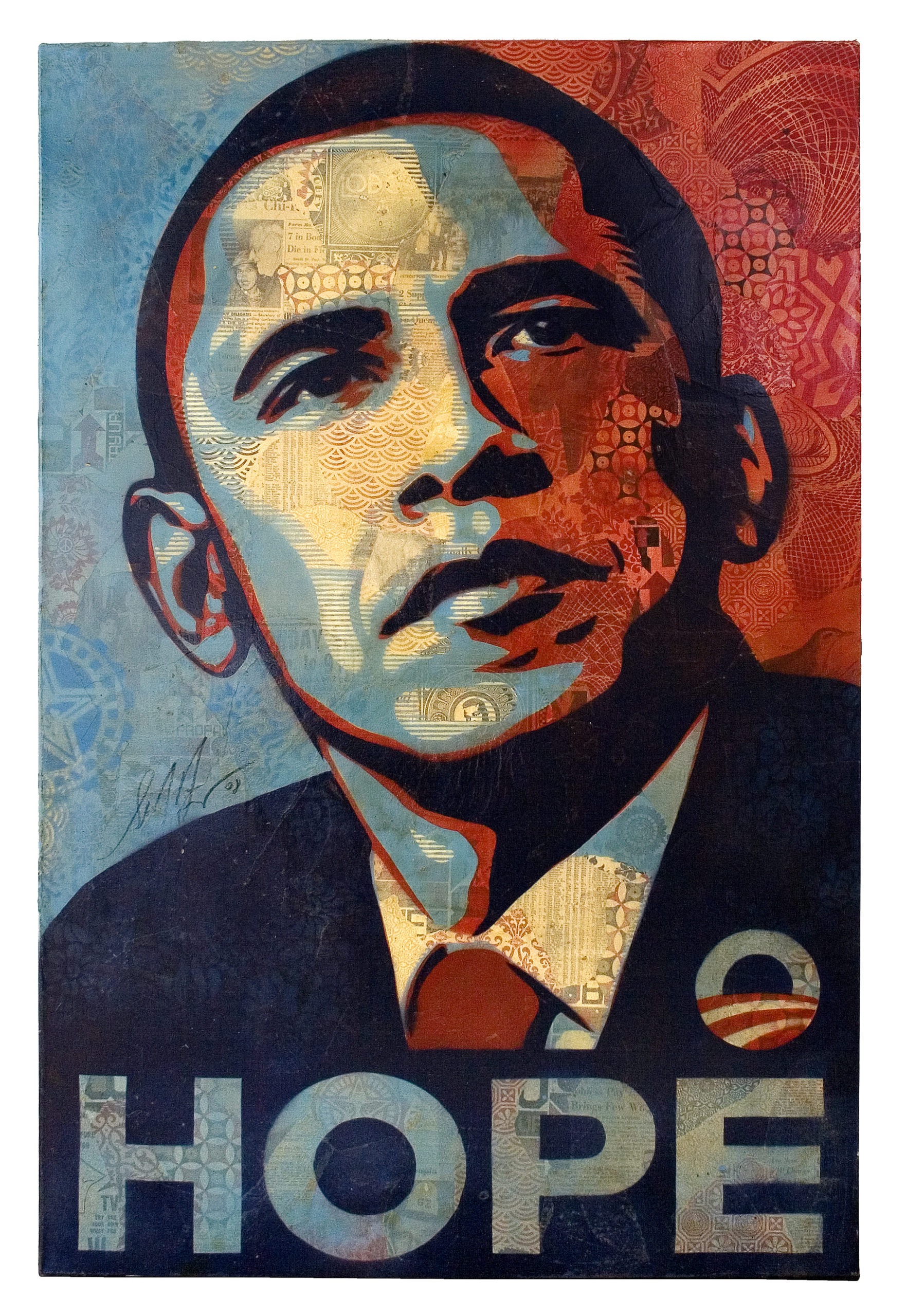

Shepard Fairey was born in Charleston, South Carolina. He received his Bachelor of Fine Arts in Illustration at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Rhode Island. In 1989 he created the “Andre the Giant has a Posse” sticker that transformed into the OBEY GIANT art campaign, with imagery that has changed the way people see art and the urban landscape. After more than 30 years, his work has evolved into an acclaimed body of art, including the 2008 “Hope” portrait of Barack Obama, found at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. In 2017, the artist collaborated with Amplifier to create the “We The People” series, which was recognizable during the Women’s Marches and other rallies worldwide in defense of national and global social justice issues.Fairey’s stickers, guerilla street art presence, and public murals are recognizable globally. His works are in the permanent collections of the Boston Institute of Contemporary Art, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and many others.

Shepard Fairey has painted more than 110 large-scale murals across six continents worldwide.

Where did your desire to create art with a message start? Was this a function of being a part of skate/punk culture where it was ok to speak your mind? Did you feel you had a responsibility to do more with your art once it started spreading worldwide?

Yes, skateboarding and punk rock were key catalysts to my approach to art as a tool of social commentary. Punk rock bands like The Clash and the Dead Kennedys, and Bob Marley made me think about the power of art mixed with social commentary. The rebellious visuals of skateboarding and punk rock encouraged me to be more outspoken with a mixture of pop art and DIY techniques. When I first started my Andre the Giant sticker campaign, which caught on virally, I thought about the opportunity to communicate in a more meaningful way with my audience. That led to the evolution of that campaign to incorporate the word “OBEY” and more overt social commentary. I think anyone with an audience is obligated to engage responsibly, but that’s not as common as it should be.

Because your art speaks to the issues/troubles we face in this country, it feels very grassroots – but your style crosses over and sells for thousands of dollars in a gallery. Why do you think it holds up so well in both arenas?

My roots are DIY, and I’m very transparent about the simple creative empowerment tools. However, I have also studied graphic art and fine art extensively to speak a universal language with my work and make the work sophisticated aesthetically. I think I’m fortunate that I’ve cultivated a diverse audience ranging from teenagers to very wealthy art collectors. Accessibility is essential to me, so I make works that sell for a wide range of prices, many very inexpensively.

How do you feel about the duality of “placemaking” and the fact that one of your murals can change a neighborhood and create social change but is also used as a marketing tool by landlords to make rents go up, etc.?

I’ve never worked with anyone whose goal was to use art to raise rents. But I think it’s better to encourage lawmakers to oversee landlords and developers than to give up on art in public because some unethical people leverage the culture around the art. The most exciting thing about art is the ability to transform spaces and attitudes. Making a large mural that is accessible and transforms the landscape creates conversations about the mural’s content and the control of the public space itself, which is one of the most powerful things I can think of.

There is a clear connection in your work to graphic design – beautiful patterns and strong use of typography. Do you use a computer to create your art at any stage, or is it all hand-done?

I use a combination of traditional and digital techniques. I am frequently working back and forth between mediums to accelerate my processes of composing and executing. I make my illustrations by hand, but then I scan them and work out color composition and typography in illustrator to yield a digital sketch. I then make stencils, screens, and collages in my art studio, working off the digital illustration but leaving plenty of room to improvise in the studio with spraypaint, acrylics, etc.

Things have calmed down somewhat in post-Trump America, but we still have so much to work on as a country. What issues are you trying to get in front of currently?

Environmental destruction and climate change are always top concerns for me. Those issues affect every human and every living thing on the planet, and I feel a responsibility to future generations to leave the earth reasonably inhabitable. Voter suppression and other threats to democracy are also a big concern. When a few bad actors whose views do not represent the majority undermine democracy, we should be incredibly concerned because almost everything that constitutes the public good is threatened.

I’ve read that as a kid; you would sit and draw for 8 hours at a time! Where do you think this focus/desire came from at such an early age? What do you think kids in current generations are missing out on by having so many distractions?

I loved drawing because of the sense of accomplishment I felt as an image materialized and was refined, but I had so much time to draw largely because I was on restrictions frequently. I was a mischievous kid and got in a lot of trouble. I hated being on restriction, but it did help me to develop my love of art and various crafts like model-making and stencil-cutting. Creativity is active, not passive, so many entertainment options and distractions are a problem for sustained focus and creativity. I know because I have daughters who are 13 and 16, and they have relatively short attention spans and love to look at their phones. They are creative, but they don’t work on anything for more than 20 or 30 minutes at a time. That concerns me. The joy and value of creative focus are learned, so I’m afraid that many kids won’t achieve the critical mass through the efforts necessary to understand their creative potential.

What does being brave mean to you?

It means speaking out for the right things even when you know other people will disagree or attack you. Making an effort to shape the world the way you’d like it to be, even when you feel overwhelmed and insecure, takes courage, but it’s essential to know that even the most successful people often feel that way.